The Historical Importance of Environmental Activism

In light of the most recent elections in the United States, I thought it pertinent to discuss the importance and history of the environmental movement. The fact that our new administration may be rolling back environmental protections and walking away from global environmental agreements makes our activism and persistence paramount. Though it may be disheartening, we must never stop believing we can make a difference. Hopefully, this post will help remind us of the impact we can make. And, as the French would say, “Viva la résistance!” (Long live the resistance!)

The history of environmental awareness extends back thousands of years. In an online article published by Greenpeace, they write:

Ecological awareness first appears in the human record at least 5,000 years ago. Vedic sages praised the wild forests in their hymns, Taoists urged that human life should reflect nature’s patterns and the Buddha taught compassion for all sentient beings.

In the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh, we see apprehension about forest destruction and drying marshes. When Gilgamesh cuts down sacred trees, the deities curse Sumer with drought, and Ishtar (mother of the Earth goddess) sends the Bull of Heaven to punish Gilgamesh.

In ancient Greek mythology, when the hunter Orion vows to kill all the animals, Gaia objects and creates a great scorpion to kill Orion. When the scorpion fails, Artemis, goddess of the forests and mistress of animals, shoots Orion with an arrow.

In North America, Pawnee Eagle Chief, Letakots-Lesa, told anthropologist Natalie Curtis that “Tirawa, the one Above, did not speak directly to humans… he showed himself through the beasts, and from them and from the stars, the sun, and the moon should humans learn.”

Some of the earliest human stories contain lessons about the sacredness of wilderness, the importance of restraining our power, and our obligation to care for the natural world.

As we can see, the idea that we should be “good stewards of the Earth” seems far-reaching throughout history. The cultures represented in the quote above come from various parts of the globe and hold many differing traditions and beliefs. Yet, they all acknowledge the importance of living in harmony with nature. As the ancient Stoic philosopher, Zeno of Citium, stated: “The goal of life is living in agreement with nature.”

Many of these ancient cultures also took steps to address various environmental issues; “Communities in China, India, and Peru understood the impact of soil erosion and prevented it by creating terraces, crop rotation, and nutrient recycling.” (Greenpeace) Furthermore, some of these cultures ventured beyond mythical stories and began to take a more scientific approach to understanding the effects of environmental degradation. “The Greek physicians Hippocrates and Galen began to observe environmental health problems such as acid contamination in copper miners. Hippocrates’ book, De aëre, aquis et locis (Air, Waters, and Places), is the earliest surviving European work on human ecology.” (Greenpeace)

However, the oldest environmental activism movement seems to have been the Bishnoi Movement in the Marwar region of Rajasthan, India. The Bishnoi are a religious sect, started by the Guru Maharaja Jambheshwar in the 15th century, that teaches the principles of ecological consciousness and environmental conservation. In 1730, many Bishnoi members placed their bodies between the local ruler and the forest trees they held as sacred to life. The Environment & Society Portal website recounts the events:

In 1730, when Maharaja Abhay Singh, the ruler of Jodhpur, needed timber to construct the new royal palace, he sent soldiers to the Bishnoi village of Khejarli with orders to fell numerous Khejri trees—which have been sacred in Bishnoi culture. On 11 September 1730, Giridhar Bandhari, a representative of Maharaja Abhay Singh, arrived in Khejarli to fell the trees. When Amrita Devi Bishnoi, a resident of the village, was alerted to the threat, she and her daughters attempted to prevent the soldiers from cutting down the trees by hugging them while proclaiming…

If a tree is saved even at the cost of one’s head, it is worth it.

In an effort to prevent their own trees from being cut down, the nearby Bishnoi villagers followed Amrita Devi’s example and embraced the Khejri trees in the area. The soldiers ignored the residents’ pleas, and 363 Bishnoi were killed, including Amrita Devi and her daughters. When the Maharaja learned of the massacre, he immediately ordered the woodcutting operation to be halted and apologized for the deaths. He also granted complete state protection to the Bishnoi villages of the region—this is no longer applicable today, but the nonhuman nature in the area is now protected by various legislations of the Indian government. In addition, the king issued a royal decree on a copper plate, prohibiting cutting trees and hunting animals within and around all Bishnoi villages. To honor the legacy of the Bishnoi’s sacrifice, the government of India established the Amrita Devi Wildlife Protection Award (ADWPA) in 2000, and 11 September was designated National Forest Martyrs Day in 2013.

Though the Bishnoi Movement is often not mentioned in the West when discussing the history of the environmental movement, another movement out of India is known in the U.S., at least in name, the Chipko Movement. “The Hindi word chipko means ‘to hug’ or ‘to cling to’ and reflects the demonstrators’ primary tactic of embracing trees to impede loggers.” (Britannica) To those who know the story of the Bishnoi Movement, the historical links between this movement and the Bishnoi are obvious. The Indian Chipko activists were undoubtedly influenced by the heroic stories they had been told about the Bishnoi people. An article on JSTOR Daily discusses the Chipko Movement in more detail:

In the contemporary United States, “tree hugger” is most often used derisively, describing people judged to care more about plants and animals than human thriving. But, as economist D. D. Tewari writes, the most significant tree huggers in modern history, the Chipko activists of 1970s and ‘80s India, succeeded by calling attention to the deep interdependence between humans and the natural world.

The Chipko movement took place in the Garahwal Himalayas, a region with dense forests that had protected it from invasion prior to British colonial rule. Tewari writes that the area had a strong cultural tradition of reverence for nature, with religious rituals devoted to trees, rivers, mountains, and local village gods…

As logging accelerated in the early 1970s, Chandi Prasad Bhatt, a former clerk who had left his job to promote social justice in the rural hills, proposed a strategy to fight tree cutting. He called it Chipko—Hindi for “hug.” Soon, Tewari writes, villagers were confronting lumbermen by shouting slogans and physically blocking them from the trees…

Ultimately, the Chipko movement managed to preserve forests across the region through a mix of women-led local action, foot marches, fasts, and strategic publicity to gain international support. Its success lay in embracing the connections between the lives of trees and the economic and spiritual lives of human communities.

In the United States, many writers addressed environmental issues throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, including authors such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, George Perkins Marsh, John Muir, Aldo Leopold, and more. And, these writings helped encourage the establishment of the National Parks and several prominent conservation groups. However, the modern environmental movement in the U.S. began in the 1960s, often attributed to the publication of Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring – which condemned the use of pesticides like DDT because of their effects on humans and nature. This led to the banning of DDT use in the U.S. in 1972. Additionally, the public awareness of human environmental impacts rose dramatically during this time.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the rise in environmental awareness and activism was also linked to the countercultural movement of the “hippies”. Britannica describes the hippie movement as such:

The movement originated on college campuses in the United States, although it spread to other countries, including Canada and Britain…

Hippies were largely a white, middle-class group of teenagers and twentysomethings who belonged to what demographers call the baby-boom generation. They felt alienated from middle-class society, which they saw as dominated by materialism and repression. Hippies developed their own distinctive lifestyle, whereby they constructed a sense of marginality. They experimented with communal or cooperative living arrangements, and they often adopted vegetarian diets based on unprocessed foods and practiced holistic medicine…

Hippies advocated nonviolence and love, a popular phrase being “Make love, not war,” for which they were sometimes called “flower children.” They promoted openness and tolerance as alternatives to the restrictions and regimentation they saw in middle-class society…

Public gatherings—part music festivals, sometimes protests, often simply excuses for celebrations of life—were an important part of the hippie movement. The first “be-in,” called the Gathering of the Tribes, was held in San Francisco in 1967. It initiated the Summer of Love, wherein up to 100,000 members of the counterculture traveled across the United States and converged in the Haight-Ashbury district of that city…

[M]any hippies participated in a number of teach-ins at colleges and universities in which opposition to the Vietnam War was explained, and they took part in antiwar protests and marches. They joined other protesters in the “moratorium”—a nationwide demonstration—against the war in 1969. Hippies were also involved in the development of the environmental movement. The first Earth Day was held in 1970, and many participated in teach-ins that educated listeners in the importance of environmental conservation…

According to the Library of Congress, an estimated 20 million people participated in the first Earth Day on April 22, 1970; they write:

[P]eople nationwide attended the inaugural events at tens of thousands of sites including elementary and secondary schools, universities, and community sites across the United States. Senator Gaylord Nelson promoted Earth Day, calling upon students to fight for environmental causes and oppose environmental degradation with the same energy that they displayed in opposing the Vietnam War. By the twentieth anniversary of the first event, more than 200 million people in 141 countries had participated in Earth Day celebrations. The celebrations continue to grow.

As we can see, activists have used various tactics throughout history to spread awareness and demand change; they have marched, written, taught (talked to others), and when necessary chose to place their bodies in the line of attack. These lessons from the past may be useful to us now. However, some of the environmental issues we face differ from those of the past activists. Karin Otsuka, a student at the University of Washington, writes on the school’s student blog:

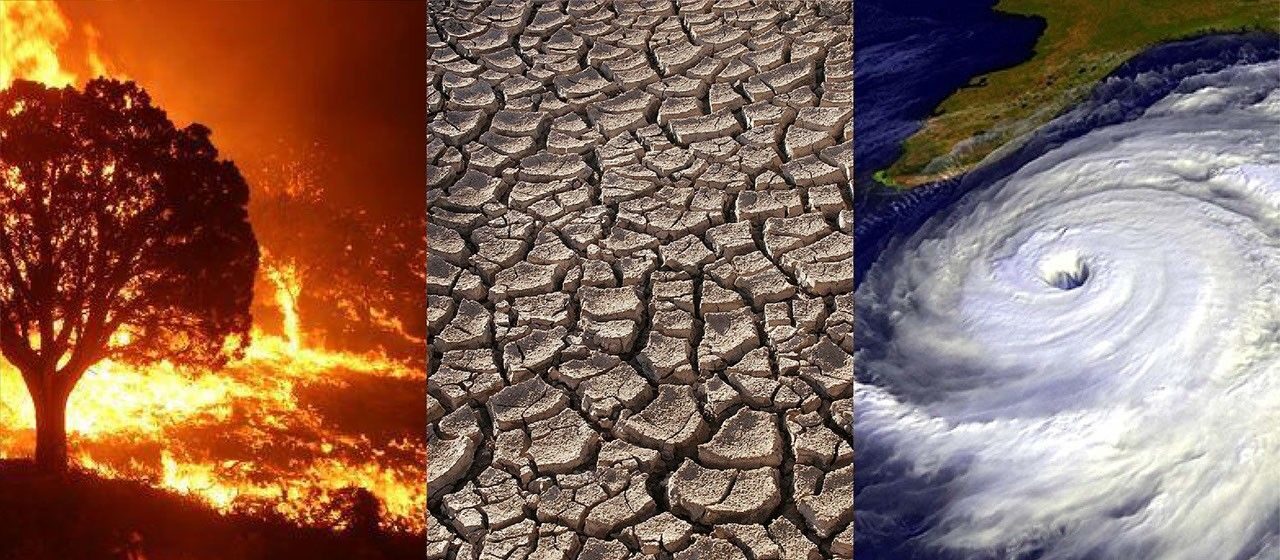

[U]ntil this point, issues of environmental degradation have been largely visible and localized, directly impacting individuals and communities. This brought on a great challenge in framing climate change, a rising issue in the late-90s and 2000s that warned against long-term impacts and was on a scale of global proportions. Topics related to climate change, such as sea-level rise, ocean acidification, frequent heat waves, and intensified storms had started to circulate in mass media by climate scientists. This fueled students, activists, journalists, and youth worldwide to begin advocating against these projected environmental impacts and their associated threats to human health.

We continue this fight today: how to encourage our fellow citizens to fight for the future.

One of the most inspiring parts of the modern environmental movement is the involvement of so many of today’s youth. Though ecological activism in the U.S. has often come from young people, such as the hippies, today’s activists are much younger, often not even out of high school. From student walkouts, like those encouraged and conducted by Greta Thunberg, to the rise in social media accounts that address the climate crisis, today’s young activists are making a big difference. In an online article by the Global Council for Science and the Environment, they discuss the impact that young activists continue to have:

[Y]outh-led organizations like Zero Hour, Earth Uprising, and Fridays for Future—all started by high schoolers—have formalized this movement, providing a platform for countless young voices to be heard…

Student activists are using individual motivation as a launchpad for collective action, a common refrain of the environmental movement. Individual actions—going vegan, taking public transit, skipping flights—help shape culture and create more eco-friendly consumer preferences (if enough people favor plant-based alternatives over meats, grocery stores and companies notice). But they are only one part of the solution.

To create real change, we need to merge these individual actions into mass mobilization. The youth movement has done just that with the global climate strikes and coordinated weekly striking, and they will continue to do so in the coming decade. There is no better space than college campuses for mobilizing the passions, intelligence, and voices of the youth movement. Students are realizing the importance of eco-conscious behaviors earlier, and it’s influencing college decisions…

The campus setting not only provides a physical space for inspired young people to assemble—it also provides an intellectual space. After the first Earth Day, sustainability in colleges became a prerequisite value, ingrained in higher education.

I hope we can all find the fortitude and courage in the coming years to continue the fight for a better tomorrow, but it will not be without its challenges. The Human Rights Watch addresses some of the challenges modern activists face:

[A]s the climate crisis worsens, the civic space for climate protests is shrinking. Instead of focusing on meeting their commitments to reduce climate change, governments are threatening environmental protectors—from Indigenous communities defending their ancestral lands to young activists protesting the expansion of fossil fuels—with intimidation, legal harassment, and at times deadly violence.

New forms of attacks are emerging, like the use of counterterrorism laws against climate activists, who are vilified in public and political discourse. And governments have been ratcheting-up their repression of such protests.

These issues extend to many of the industrialized nations around the globe. Therefore, we must remain steadfast yet vigilant. We will have to continue to search for innovative ways to engage the public and industry alike. May our hearts remain dedicated to the good fight.

Featured image: https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-suspected-banksy-mural-london-supports-environmental-protests

Life is no game of private theatricals, as WIlliam James said. If it were, we could just exit the play. But “it feels like a fight,” and it’s heartening to be reminded that we’re not in the fight alone. Not even generationally. But it’s our turn to step up.

Thanks, Kathryn. Carry on!

Yes, it is our turn. And, thanks, in part, to your teachings, I am ready for the fight. Thank you!